Toolbar

Biographies & Autobiographies | 41 Chapters

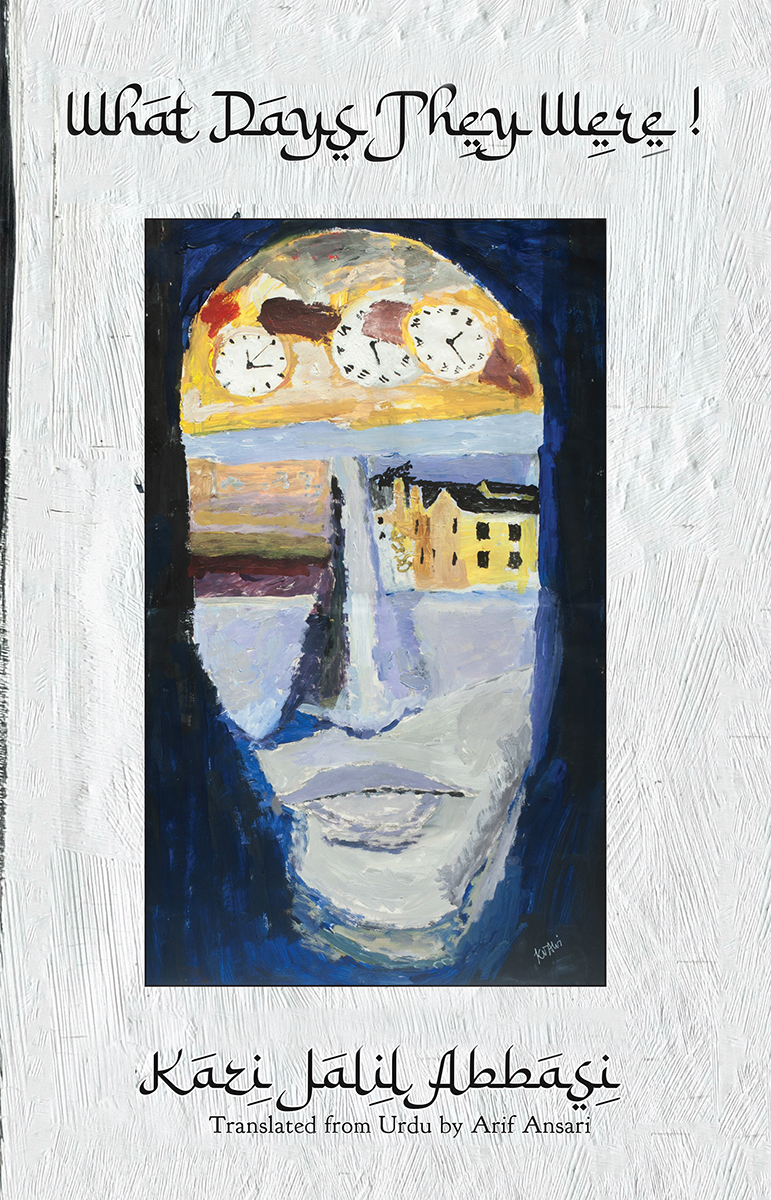

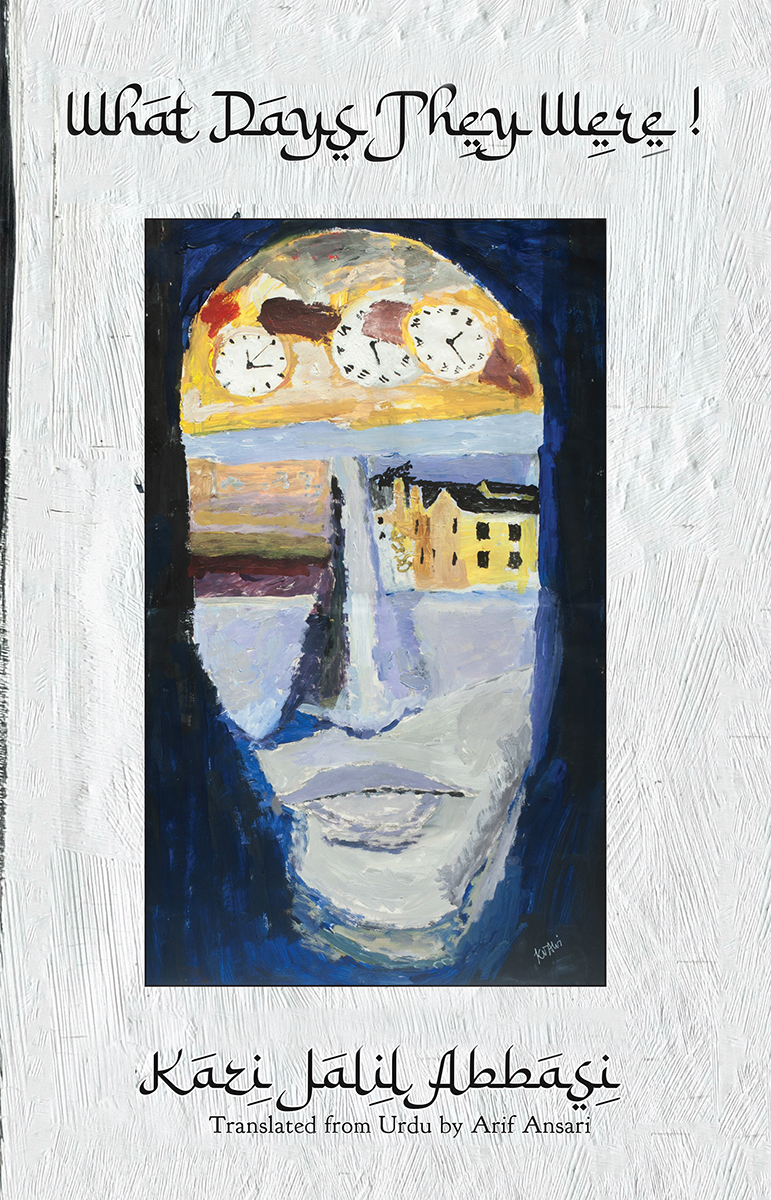

Author: Kazi Jalil Abbasi Translated from Urdu by Arif Ansari

Kazi Jalil Abbasi was born in the village of Bayara, district Basti, in Uttar Pradesh state. He attended schools in Basti, Gonda, and Unnao. He was educated at Aligarh Muslim University, Arabic College in Delhi, and Lucknow University. He was an agriculturist, freedom-fighter, lawyer, and a politician. He represented the Domariyaganj constituency of UP in the seventh and eighth Lok Sabha of the Indian Parliament. This book is an English translati....

Kazi Jalil Abbasi was a friend of my father, Anwar Ansari. His larger-than-life personality, with his booming voice, was a frequent and welcome guest at our home in Aligarh. In his starched white khadi kurta and churidar pajama, and the white Gandhian cap, a khadi-wool vest on top in winters, he looked the quintessential Nehruvian politician, but I always sensed there was more to him than that stereotypical label. When he visited, my father’s relaxed demeanor and joviality, uncharacteristic of his otherwise reserved and serious-minded persona, suggested a deep connection between them. It is not clear to me what that connection was, given that Jalil Abbasi was expelled from Aligarh Muslim University in 1937, the year my father entered the University as a freshman undergraduate. My father spent the rest of his life in Aligarh, other than the few years spent abroad for his doctoral studies and post-doctoral research. Jalil Abbasi did not return to Aligarh to live there. Perhaps this photograph holds some clues to the answer:

The photograph is from room number 4, Mumtaz House, the hostel room at AMU of the three students pictured. It was probably taken a few years after Jalil Abbasi’s expulsion, but his legacy is palpable. This room is down the hall from room number 43, where Jalil Abbasi lived when he was studying at AMU, or, more accurately, held court every evening in sessions that lasted late into the night, boisterous gatherings of conversations, laughter, and endless rounds of tea. Nehru’s portrait on the wall suggests an allegiance to Gandhian philosophy and Congress politics, two of the three attributes that near-completely defined Jalil Abbasi.

On the left is Siddiq Ahmad Siddiqui, or Chacha Siddiq as he was known to his fellow students. (For popular culture enthusiasts, he was the father of Zubair Ahmad Siddiqui, the London-based theater actor with the stage name Marc Zuber, who also acted in a few Bollywood films in the 1980s.) Jalil Abbasi has described Chacha Siddiq as his sort-of local guardian, but they appear more like partners-in-crime in the many political agitations that Jalil Abbasi spearheaded while in Aligarh.

In the middle is Ziaul Hasan, my Acche Mamun because he later became my father’s brother-in-law, having arranged for my father and his sister to be married. The copy of Jalil Abbasi’s Urdu memoir, ‘Kya Din The!’, that I found in my home, Mishkat, in Aligarh, had Ziaul Hasan’s name inscribed in it in Urdu. Quite frankly, that inscription jogged my curiosity and was perhaps the most compelling reason for my picking it up to read. Ziaul Hasan’s elder brother, Ghulam Yazdani, my Mamujan, was a close childhood friend of Jalil Abbasi, possibly from the time when they were both growing up in Basti in eastern Uttar Pradesh. Jalil Abbasi visited Ziaul Hasan at his home in Moscow, when the latter was working there as a correspondent of the Indian leftist newspaper, Patriot, and the former was visiting as a member of an Indian delegation to the World Peace Conference. One of the founders of the Patriot newspaper was the well-known leftist leader, Pandit Keshav Dev Malaviya, a close friend of and mentor to Jalil Abbasi.

On the right is my father, Anwar Ansari. In an interview with BBC-Urdu Service, shortly before his death in 1978, speaking about the influence of the Muslim League in Aligarh, he remembers that “When I came to Aligarh in 1937, the Muslim League had no influence there. I remember well, in 1936 a resolution was presented at the University’s Students’ Union to establish a “Muslim Students’ Federation”. The resolution was defeated…” Kazi Jalil Abbasi’s fingerprints are all over the defeat of that resolution. In fact, the secular and anti-sectarian sentiments were so fundamental to Jalil Abbasi and his ilk, that they did not rest there. Sometime later, Jalil Abbasi, Ansar Harvani, Farhatullah Ansari, and a few others traveled to Lucknow to thwart the Muslim League’s second attempt to form a separate Muslim Students’ Federation at a convention in Lucknow, visiting Firangi Mahal, my father’s ancestral home, to garner support from Jamal Mian, a rising political star with influence over Muslim League politics. This was the beginning of a set of lifelong values that defined Jalil Abbasi, which can best be summarized as follows—Jalil Abbasi was a hard-core Aligarian, even after he left Aligarh, and perhaps even before he came to Aligarh. It is the third attribute that completes the definition of Jalil Abbasi’s personality and character. To use a cliché, Aligarh may have expelled Jalil Abbasi, but Aligarh was never expelled from within him. Anwar Ansari too was a lifelong Aligarian, having entered AMU as a 17-year-old undergraduate freshman, and reaching the stature of Senior Professor of Psychology and Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences at the time of his death 41 years later. I like to think they were kindred spirits in that regard.

This book is an English translation of Kazi Jalil Abbasi’s Urdu memoir, Kya Din The! (What Days They Were!). From the beginning of his life in a village called Bayara, by way of early political activity in schools in Basti and Gonda, to student agitations and freedom movements in Aligarh, Delhi, and Lucknow, on to practical politics in the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly, Uttar Pradesh Cabinet of Ministers, and the Indian Parliament, culminating in a presence in the inner-circles of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi—what a story!

Unlike a previous translation of an Urdu book from the same genre, I have not included any foot-note translations, notes and explanations beyond what has been included in the main body. I encourage the reader to use internet resources, such as Google and Wikipedia for general information; Google Translate and Rekhta.Org/urdudictionary to translate Urdu words (both websites allow entry of words in the Roman script while the former also allows the use of an Urdu keyboard to enter the word in Persian script).

I would like to thank my daughter, Asna Ansari, for reviewing the manuscript and Notion Press for all their help in publishing this book.

Dedicated To the memory of my late brother,

most honorable Kazi Muhammad Adeel Abbasi

Whose heartwarming personality has always

been a beacon of light for me.

Laws of bold men fearlessly speak the truth

Lions of God know not how to be cunning

Biographies & Autobiographies | 41 Chapters

Author: Kazi Jalil Abbasi Translated from Urdu by Arif Ansari

Support the author, spread word about the book to continue reading for free.

What Days They Were!

Comments {{ insta_features.post_zero_count(insta_features.post_comment_total_count) }} / {{reader.chap_title_only}}

{{ (txt.comment_text.length >= 250 ) ? txt.comment_text.substring(0,250) + '.....' : txt.comment_text; }} Read More

{{ txt.comment_text }}

{{txt.timetag}} {{(txt.comment_like_count>0)? txt.comment_like_count : '' }}{{x1.username}} : {{ (x1.comment_text.length >= 250 ) ? x1.comment_text.substring(0,250) + '.....' : x1.comment_text; }} Read More

{{x1.comment_text}}

{{x1.timetag}} {{(x1.comment_like_count>0)? x1.comment_like_count :''}}{{x2.username}} : {{ (x2.comment_text.length >= 250 ) ? x2.comment_text.substring(0,250) + '.....' : x2.comment_text; }} Read More

{{x2.comment_text}}

{{x2.timetag}} {{(x2.comment_like_count>0)?x2.comment_like_count:''}}