I like the smell of old tea.

Not the fresh one—they put ginger in that now, burns my nose. No, I like the one that spills out of the broken bhars, the one the crows step in before I do. Sometimes it smells like dreams. Sweet, burnt dreams. I crouch by the dustbin near Ghosh’s Tea Shop and press my nose to the cracked clay, licking the rim where someone else's mouth once touched. Warm once. Now cold. Like me.

They say I’m mad. Pagli. Hah. Maybe. Maybe not. But I remember. Not always, but when I do—it stings.

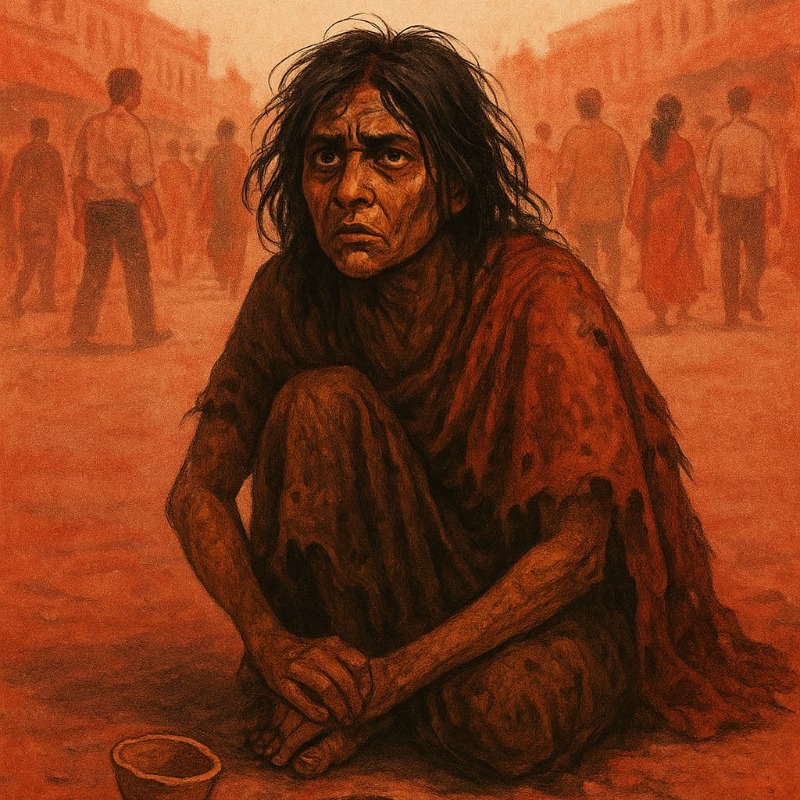

I sit here every day. Same spot, near the drain where the tea mixes with spit and paan-stained water. From here, I see everything. The hawkers yelling, the buses coughing black smoke, the fat man scratching his belly while selling underwear on a hook.

And I see how they see me.

They don’t really.

They walk around me like I'm a crack on the road. Like I’m a street dog. No—not even that. People feed dogs. They call them “Tommy” and “Browny” and give them biscuits. Me? They wrinkle their nose. Step back. Mutter: “Uff pagli abar ekhane boshe ache.” (Ugh, that madwoman again.)

Sometimes some kid throws a coin at me—

And I throw it right back.

Hit him on the face if I’m lucky. I scream at him, cuss his whole family. Mother, father, grandmother, even the pet cat if they have one.

They think I’m a beggar? Think I need their two-rupee mercy?

They think I want an inch of their property?

Hah. If they only knew.

But I don’t remember what I knew, don’t remember what or why or who. Every second splinters into a vacuum in my mind. And the people around me are merely shadows, wearing long sparkling clothes. A black fog overrides my head, and once in a while a sound from the screeching traffic jam comes around, hits me over the head and I go marching. I go marching, jumping, to cut through the fog. Only, everytime I do that, the air reverberates with this loud gran, screams of agony. Feral, animalistic sounds and then I’m jumping over hoops trying to finds it’s source, only to realise that the animal was me all along.

But today, the fog thins.

A gust of wind brings a strong scent of perfume. Not like the jasmine oil Didi used to wear, no, it’s sweeter- almost artificially sweet. Like talcum powder mixed with lies.

Three women pass by, heels clacking, bangles clinking, voices sharp as glass.

One of them laughs and says,

“You’re acting like it’s a hard job to do. Just mix something in his tea- trust me, that will do the trick!”

The others laugh. Too loud. Too long.

And just like that, my memory splits open.

Her face.

That voice.

That laugh.

The woman with the glittering dupatta. Her teeth too white, too sharp.

It might be her.

It might be the one who made me drink the milk that never let me sleep again.

The one who signed a paper. Sold my house.

Called me “pagli” even when I wasn’t. Or was I?

The black fog returns—but this time, it burns red.

I don’t think.

My legs move before the thought finishes in my head.

I lunge.

She doesn’t see me coming. None of them do.

My nails claw at her shiny dupatta, tear at her blouse, I slap her face, screaming.

“You! It was you, wasn’t it? You mixed something in my milk, didn’t you? I had everything—everything! Why did you take it? Why did you take it?”

She shrieks. Her friends scatter. One of them screams for help.

But no one comes to get me off her.

A whole market of men and women and young boys in jerseys and old men chewing paan—all of them just standing there.

Phones out.

Mouths open.

But then it all vanishes.

I don’t hear the crowd anymore.

I don’t see the market.

The dust disappears.

The honking vans vanish.

I’m home.

The veranda smells of coconut oil and ripe jackfruit. My feet are pressing down on the red oxide floor. My uncle stands near the threshold, holding papers in one hand, a bottle in the other.

“This is your signature, Shiuli. You agreed to it. You can’t say no now. You can’t!”

Liar.

Thief.

Snake.

They’re dragging me by my arm, trying to tear the gold bangles off my wrist. Tears stream down my cheeks as I clench my nails into their arms, my voice reverberating through the lengths of the hallway that my father had built, brick by brick.

“This is my house! My father left me this house! You can’t- you can’t kick me out!”

I hit someone. A face. A cheekbone. A shoulder.

They’re not stopping. No one stops them.

I blink.

The world tilts.

The jackfruit trees are gone.

So is the red floor.

Only grey concrete, red blood.

I’m crouched on the road again. My knees ache.

My hand is soaked—sticky. My breath is ragged.

Beneath me, the woman lies broken like a dropped doll.

Her face—unrecognizable. Swollen, bruised, her nose bleeding.

Her voice trembles: “Someone…please… help…”

But no one comes.

They all stand around—phones out, lips curled.

One man mutters, "Are you crazy? What if she beats me too!”

Another says, "Stay away! Madwomen don't need reasons."

I look down at my trembling hands.

At the woman I thought I knew.

But maybe I didn’t.

Maybe I do.

The fog creeps back in.

I don’t realise when the woman is taken away. Don’t realise when a police van struts in, the sound of the siren reverberating in the air like my voice in every corner of the house that they made me leave behind. I just sit there, staring at the blood on my hands. There’s an ambulance. Did someone die here? Why are these people dragging me into the van?

Where are these sounds of wailing coming from?

I crouch down to look through the gaps of the cell, but I see nothing.

The black fog has turned opaque.